Focus on our 50th: Planners as ‘Environmental Strategists’

18 May 2022

Planner and Boffa Miskell Partner, Robert Schofield, reflects on the benefits of working within an integrated multi-disciplinary company, based on a strong ecological ethos.

When I was first approached by Frank Boffa in the mid-1990s to join Boffa Miskell, I had been working in a large multi-national engineering-focused company for most of my career as a planner. The invitation to work with a wholly New Zealand-owned and highly respected company, where planning was not a tack-on but an integral part of the company’s services and ethos, was gratefully accepted. I had already worked alongside Frank and others in Boffa Miskell on various projects, and I admired and respected the energy and integrity of the ‘Boffa Boffins’.

Professionally, I believed that working collaboratively with the special mix of expertise within the company every day – landscape designers, landscape planners, ecologists, urban designers – would provide a synergy of knowledge and expertise that would underpin my own professional direction and interests. And so it has proved.

Boffa Miskell’s evolution into this uncommon but successful combination of disciplines – one that others have tried to emulate since – has proven not only to be a robust commercial model, but one that has been somewhat prescient in terms of addressing many of the issues facing New Zealand in the early 21st Century.

Some 14 years ago, following research I undertook into planning trends in the UK and Australia, I wrote a think-piece for the New Zealand Planning Institute in which I set out some of the key issues facing the planning profession, and the struggle we were having in making real progress in addressing New Zealand’s environmental problems under the RMA. In my paper, I described the principal challenge for New Zealand was to have an environmental management framework that could deliver meaningful outcomes. I further noted that, for all of its strengths, the RMA was unlikely to fully achieve environmental sustainability – for example, it is poorly set up to address the increasing water allocation issues this country is facing. I concluded that:

Consequently, I have little doubt that there will be major changes to our planning system within the foreseeable future, although it is unlikely that the core features of the RMA will be discarded, as the integrated participatory planning framework that it provides has been too well tested, fine-tuned and widely accepted to “throw the baby out with the bathwater”.

The paper was intended to promote a discussion within the planning profession as to what changes are needed to help planners have a more proactive (rather than reactive) role in environmental management. And vice versa: what could planners be doing to facilitate a more outcome-based framework? Unfortunately, under the RMA, planning had become increasingly reactive in nature, responding to change rather than being the agent – or catalyst – of change.

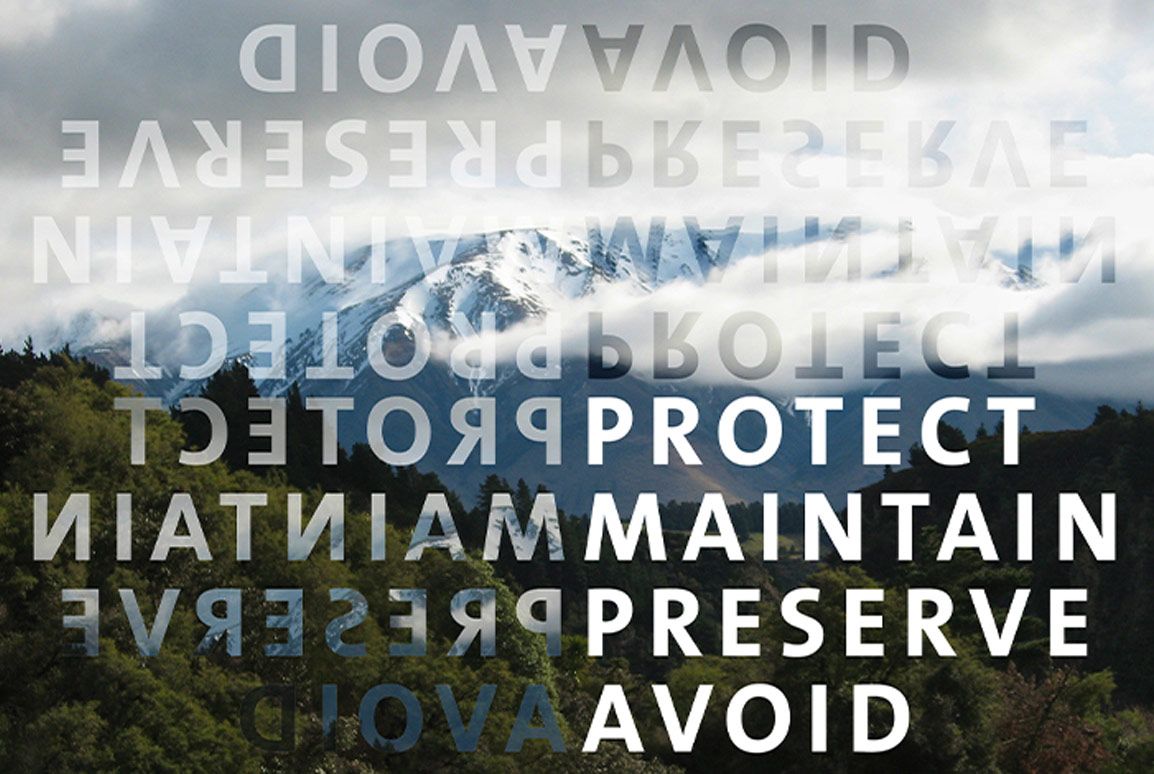

The statutory ethos since 1991, under the effects’ management paradigm, had developed into one seeking “to protect”, “to maintain”, “to preserve”, “to avoid”. While there is obvious need to protect our environment from the worst effects of human activities, planning in my view should be focused on achieving wider and more positive outcomes: helping to improve degraded environments, not just preventing further degradation; helping to shape our urban environments, rather than protecting people’s amenity values.

In my article, I predicted that, in future, there will be more of a need than ever for the proactive planner, the professional who can investigate, identify and articulate environmental visions and evaluate and establish effective courses of action for achieving those outcomes. I urged the profession to avoid being called a ‘specialist generalist’ (as I’ve heard many planners call themselves), but rather develop skill sets in being enablers, scenario-makers, provocateurs and independent arbiters. In other words, I envisaged planners of the 21st Century as being ‘environmental strategists’, helping shape the future of our cities and towns, and turning around the degradation of our natural environment. Such skills would be necessary if we are to make meaningful change.

We now have a proposed replacement statutory framework for the RMA, the Natural and Built Environments Act and Spatial Strategies Act, in which I believe the skills of such ‘environmental strategists’ will be critical to its success. The planning profession has already started as to how our role will change under this new structure: what does outcomes-based planning look like, as opposed to effects management planning? How can we create Plans that actually achieve some very hefty and lofty goals so we make real environmental progress?

Working at Boffa Miskell places planners in a good position to develop their skills as environmental strategists. We are working on a daily basis with professionals who know how to envision, create scenarios and be provocateurs. The company has the tools and expertise to support such processes, as well as the thinkers who can think strategically and spatially. We have the specialists who apply ecological and design principles ‘on the ground’ and can see the Big Picture in terms of the many interrelationships and systems that make our natural and urban environments function.

If the new statutory framework is introduced (I worry that time will run out this Parliamentary term), every Boffa Boffin could have a very real role in contributing towards its successful implementation, not just planners.

Find out more

Focus on our 50th: Moving forward as we look back

Focus on our 50th: The evolution of 'Applied Ecology'