Be Bold: Lessons learned from Infrastructure Projects

29 April 2020

As the phrase “shovel-ready” enters New Zealand’s vocabulary, it’s worth pausing to think about what that adjective really means.

A shovel-ready construction project (usually larger-scale infrastructure) is one in which preliminary planning, resource consenting and engineering is advanced enough that with sufficient funding, construction can begin within a very short time. The phrase was popularised by US President Barack Obama during the stimulus funding of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.

The fast-tracking of infrastructure has long been a useful tool for lifting economies out of recession and was exemplified in the post-Depression era by American public official Robert Moses. His decisions favouring highways over public transit and hydroelectric dams over ecosystems influenced a generation of engineers, architects, and urban planners who spread his faster-is-better car-centric philosophy across that nation.

With nearly a century’s worth of hindsight, modern urban designers, landscape architects and ecologists view Moses’ legacy with a mix of awe and horror. A particularly egregious example is Delaware Park, in which a dual-carriage motorway was ploughed straight through one of Frederick Law Olmstead’s 19th Century masterworks.

But that’s America, you’re thinking.

Here in New Zealand, we don’t make those sorts of mistakes.

Really? Just a few decades ago (in a manoeuvre lifted straight from Moses’ playbook) the Ministry of Works extended Auckland’s Mount Roskill to Wiri motorway. Onehunga’s original beachfront esplanade was removed, the Southwestern Motorway (SH20) was built across Onehunga Bay and residents were effectively cut off from the water.

The deservedly awarded Taumanu Reserve has gone a long way to putting salve on the wounds of the past, but the scars remain — both on the land and, crucially, in the hearts and minds of residents.

In talking of ‘shovel-ready’ projects it’s typically noted that planning and engineering has been progressed — but the status of community consultation and engagement concerns often go unmentioned.

For many of these projects community engagement and ecological assessments have been an integral part of the ‘planning’. And in New Zealand we do have a recent history of ‘doing things better’ as evinced by projects like the Waikato Expressway and the adjunct restoration of the Paa and wetlands at Rangiriri; and of course, the much-lauded Waterview Connection and its many positive ecological, community and social outcomes.

In our understandable urgency to administer a shot of adrenaline to the national and regional economies, we must remember that community engagement shouldn’t stop when the shovels and diggers arrive. Mitigating the impact of the on-going construction disruption is essential if we hope to build on what we’ve learned from the past few years of infrastructure building, and take those valuable lessons into the post-COVID reality.

Lesson #1) Relationships matter

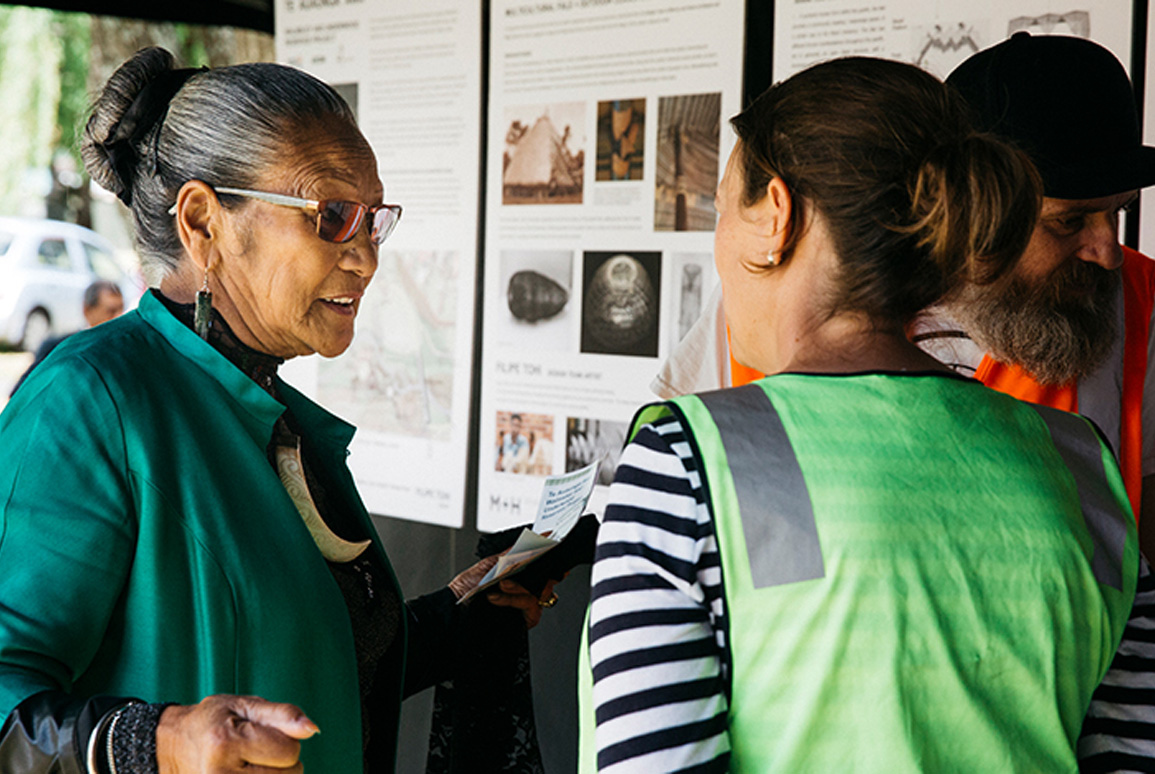

Community buy-in matters; and making soon-to-be-disrupted locals feel heard and valued does not come through a talking head presenting on a screen. Nor does a prefab on-line survey, however well-intentioned, foster the open dialog and follow-up questions that face-to-face conversation does. So here’s where we need to do some thinking. If we agree that engagement needs to continue, in as close to normal quality as possible how might that work in a world where hongis and handshakes are now forbidden?

Do we need to have meetings to talk about how to have meetings?

To some extent, yes.

Lesson #2) Experience counts

If we’re seeking to bring about efficiencies, and progress a large-scale project on multiple front simultaneously, it’s essential to have a team of project partners with the experience to make that happen. There’s no time for learning curves. The alliance model has the advantage minimizing internal conflict within the team of multiple consultancies that would otherwise arise over costs and professional territory protection.

It comes down to teamwork, just as it does in as in sports. As one player is running with the ball, teammates need to be running just as hard to be in the right spot to receive a pass. Or out in front, moving obstacles out of the way.

In the MacKays to Peka Peka Expressway project, for example, Boffa Miskell was a partner in both the consenting and construction alliances. This start-to-finish approach meant that aspects of detailed design were carried out in parallel to the construction phase.

Lesson #3) Standard processes are fine. Standard solutions are not.

In our view, there are critical elements to ensure that infrastructure projects are not just foisted into affected communities, but can be better integrated into the local context with a good level of community input. The concern with ‘fast-tracking’ shovel-ready projects without enough on-going engagement is that local community gains will be eliminated – or will be done the wrong way. As we look to leverage our experience and lessons learned, we need to avoid falling into the trap of one size fits all. A daylighted stream and outdoor recreation facilities were the right answer for Waterview. That doesn’t mean they’re the go-to solution for every community.

There will always be some tension between the cost of delivering infrastructure and good community outcomes such as those achieved by Waterview Connection, M2PP, Victoria Park Tunnel and Northern Corridor Improvements.

At Boffa Miskell, we believe that if agreement on outcomes can be achieved early it could help facilitate faster delivery of projects. This fits with the view of our current government that infrastructure delivers a wide range of benefits from enabling urban development and regeneration, multimodal transport options and community benefits.

Speed and holistic solutions need not be mutually exclusive. Fast-tracked projects that disregard the importance and value of timely and respectful community engagement will encounter significant difficulties. It is false economy to skimp on community engagement in favour of speed. While the emphasis is on getting people back to work on shovel-ready projects, New Zealanders are not going to accept this at the cost of poor environmental and community outcomes.

We’d do well to bear in mind the saying “Be quick, but don’t hurry.”